Fishing rights may not sound an exciting topic, but for people researching their family history, they can be an unexpected source of ‘treasure’.

Signs saying ‘no fishing’ are a familiar part of our landscape today. And amateur anglers need to know who owns what, and what retrictions there are on catches, before setting out with a rod.

For a start, you need the correct licence (there are two), but that doesn’t give you the right to fish where you like. Because that depends on who owns the fishing rights for the stretch of river/lake/canal, etc. And then there are close seasons, and catch restrictions.

Fishing rights in the past, as today could be complex.

Fishing rights in the past

At its simplest, the lord of the manor was usually deemed to hold the right to fish in rivers and lakes within the manor.

But this could become complicated if he sub-let those rights to tenants, or tried to charge anglers rents for fishing at spots they claimed were ‘free’.

Fishing in the Solway

My book, Port Carlisle, a history built on hope (sales in triple figures!)

has a chapter on fishing. It explains the tradition of haaf net fishing, and arguments between locals and the lord of the manor over fishing rights.

You can also read about haaf net fishing in a previous blog post:

Fishing rights 1773

The manorial records for the barony of Burgh include the following entry from 1773, which contains a certain amount of grovelling!

Whereas Sir James Lowther, baronet Lord of this barony, hath lately commenced an action at law against us John Purdy and John Pattinson for having taken two sturgeons (the property of the said James Lowther, in right of his said barony) and sold and converted at the same to our use Now, Sir James Lowther, having been graciously pleased upon our application to him to stop all further proceedings against us, upon our acknowledgement of the fact and payment of the money which we see received for the sale of the said sturgeons We do here by engage and promise we will not for the future be guilty of the life offence and return thanks to Sir James Lowther for his great clemency in not further prosecuting us –

Signed

John Purdy, his mark

John Pattinson

Witnessed by John Hodgson, and William Liddell

Other manorial rights

The records around that time also include an action at law taken by Sir James Lowther against Jonathan Simm, ‘late master of the sloop called the Farmer, of which we Isaac Fletcher and company are now owners and proprietors’.

It seems Jonathan Simm had refused to pay anchorage fees whenever the Farmer cast anchor within the barony. Isaac Fletcher and co say they didn’t know this was going on and certainly hadn’t authorised it. And Sir James was again going to stop the prosecution as they were going to pay up the anchorage money in arrears.

And in 1774, it was John Huntingdon up before the manorial court. John Huntingdon was a customary tenant of the barony and had ‘lately cut down, taken away and converted to his own use diverse timber trees and the wood which grew up on his customary tenancy in East Kirthwaite, in the manor of Thursby, within the barony.

Sir Jame Lowther had launched proceedings against John Huntingdon in the High Court of Chancery. But John Huntingdon had agreed to pay the value of the wood and his lordship’s legal costs, which Sir James had again, been ‘gratiously pleased to accept’.

We are talking about Wicked Jimmy Lowther here, but he wasn’t the only land owner to expect recompense from tenants or others on his land or in his rivers.

Back to fishing

Over in Ainstable, in 1786, some serious cases of fishing without the right to do so saw the two offenders locked up for a while in a notorious London prison.

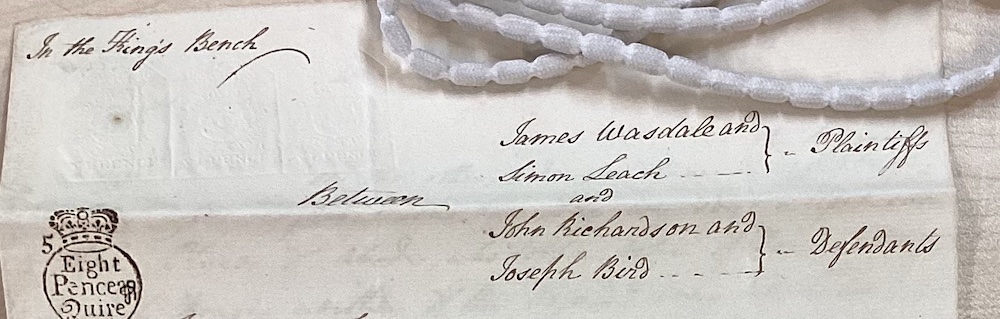

Joseph Bird and John Richardson were each (separately) charged with several counts of taking fish to the value of £100 – about £11,000 in today’s values.

In 1786, James Wasdale and Simon Leach rented land at Ainstable that included ‘a certain close covered with water called the River Eden’.

The fishery was let to them jointly by Lord Carlisle (Frederick Howard, the 5th earl, of Naworth Castle)

On Jan 2, 1786, and at least three other occasions, Joseph Bird was said to have broken in and trespassed there, ‘by force of arms’. John Richardson was accused of doing the same.

Each time, it was reckoned they had taken 500 salmon, 550 whitings, 500 pikes, 500 trout, 500 perches and 500 eels.

‘Before the King himself’

The case was initially set to be heard at Westminster, ‘before the King himself’. But it was later suggested it could be transferred to Carlisle.

The plaintiffs kept demanding pleas. The defendants kept seeking more time to enter pleas.

Meantime, Lord Carlisle’s lawyers got involved. The concern was to show that he owned the fishing rights, and Richardson and Bird had no right to fish in the river opposite their own land.

His legal team concluded he did own the rights, and Richardson and Bird’s tenancies didn’t give them permission to fish.

Both defendants gave in in the end, and pleaded guilty. Lord Carlisle’s team drew up ‘an instrument’ in order to prevent their ever attempting in future to set up any pretended right of fishery.

Whether James Wasdale and/or Simon Leach ever did get compensation for the incredible numbers of fish isn’t in the Howard records, which only cover his lordship’s side of things.